Insights

May 28, 2025

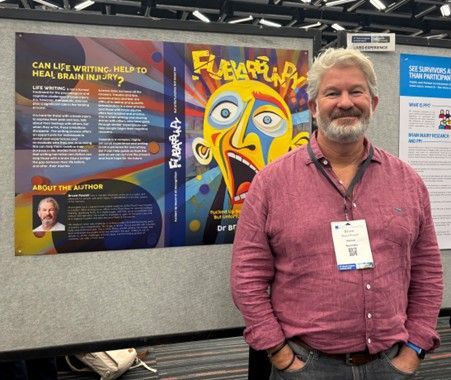

Voted the Best Poster at the World Congress on Brain Injury in Montreal. What a journey, halfway across the world to offer my poster to the World Congress and what a pleasure to be voted the winner. The conference itself was worth the trip and I look forward to maybe contributing more when the next event occurs in Valencia, Spain 2027. A massive thanks to the organising committee and all the fascianting, driven, passionate clinicians I met there. Bruce.

May 2, 2020

Starting a new job is confronting and disconcerting. The day before, you knew what you were doing, you were an ‘expert’. Now that you have been promoted or recruited, ironically, you’re clueless. You will definitely figure it all out, but the first few days constitute a crisis. Medicine is especially prone to that phenomenon and the accompanying anxiety that comes with moving one-step closer to the absolute responsibility for each patient’s well-being. The State Medical Director for Organ and Tissue Donation was a very large step indeed. High profile and politically tricky, the unique part about donation was that without our community’s engagement, belief and trust in us, there was no donation. It wasn’t ‘my’ service, nor anyone else’s at DonateLife. We were merely the facilitators of a life-saving process that had no ceiling to its budget, no limit to the number of retrievals we could potentially do, except those set by the public’s willingness to donate part of themselves, to someone that they would never meet. I witnessed my first organ retrieval as a houseman, looked after kidney transplant patients as a nephrology registrar, anaesthetised for organ retrieval and implantations and finally cared for donors and their relatives on intensive care unit. With increasing experience and fewer chance of surprises, comes a vague whiff of arrogance, even for the humblest of us. I was already an ICU Head of Department and now a whole Australian State’s solo representative on the national ‘Organ and Tissue Authority’. I was practically a God and divinity can make social engagements particularly enjoyable, since our community holds a special place of mystery and intrigue for organ donation and transplantation. “Do they take your organs before you’re dead?” took a bottle of Corona to dispel. “Has anyone ever woken up after their heart was removed” took only a mouthful of nuts to deny. Whereas “how come my relatives can overrule my decision to be a donor” could take a half bottle of wine to cover the legalities and the rationale. In fact the questioner needed the other half of the Sav Blanc to stay enthused. It had only been a few weeks but I had it pretty much covered already. Our community knew so little about donation that even the range of questions was predictable and limited. “Are you in charge of organ donation?” a lady asked as she approached me and my newly acquired sausage from the BBQ. I instinctively hoped this was the second “has ever anyone ever woken up…..” question. If it was, the sausage would outlast my answer. “They threw my husband away.” That was a first, as an opening gambit at a BBQ. The novelty of the introduction was in itself, disconcerting, irrespective of the images it conjured. “He had a brain tumour. So they just threw him away.” I gazed thoughtfully down into the heart of my sausage/bap/onion combo and wished it was a bottle of Gin. “They never told us that he could have been a donor. Never asked us. Just dumped him in a hospice and waited for him to die.” I tried to formulate an opening line through the beer, wine and nuts, still staring at my onions but missed my slot in the discussion. “Me and my kids don’t get to go to any services of thanksgiving. Have him remembered for saving someone’s life.” “Just threw him away.” “Why didn’t they ask me?” I sort of knew the medical answer to that conundrum, but from the other side, that reasoning didn’t stand up to scrutiny. I would have to find answers for us both.