Brad’s Circadian Rhythm

Hundreds of boys file into the school hall. Lines of plastic chairs are filled neatly, without gaps, not like a church or a footy stadium. This community sits shoulder to shoulder. Sure, they’re told to, but it looks natural. No one sits alone. No one is isolated by skin colour or footy allegiance. They wear uniforms and neat hair, sing their songs, and reply to prayers with one voice.

I march in behind the shrill song of the bagpipes with other members of the assembly team. I can feel emotions bubbling in my chest. Ritalin and coffee will do that, but the low hum of bagpipes and a sea of young faces would be enough to break the most stoic of observers. I stare at the floor, steadying myself. I’ve got to stand up and speak soon.

Today’s assembly is about neurodivergence and tolerance for all kinds of humans, every taste and vision. I hope none of these kids have read my grumblings about ADHD labels. I’m pretty sure they’ve got better things to do.

Earlier, I met the assembly team at the Inclusive Education Centre and was introduced to Brad (not his name). He’s tall and charming. Fifteen years old, curly-topped, and smart.

“I’m tired,” he says, straight off.

I offer him my usual brand of sarcasm, aiming for a laugh. Big mistake.

“It’s because of my circadian rhythm,” he explains. “I row. At 4:45. Every morning.”

Plonker. Too busy trying to be funny instead of listening. Now I see him. My teacher friend, an expert in all things neurodivergent, shuffles closer, looking worried. My brand of humor doesn’t always read as empathy.

“Your steroid levels go up and down,” I say, the nerdy schoolie in me resurfacing. “That’s why you’re cold early in the mornings.”

Brad looks curious. “Really?”

“Yep. When Australian athletes compete overseas, they adjust their body clocks to perform better.”

“How?”

“They train at night and sleep during the day.”

“Maybe I should try that.”

“I doubt school, or your Mum would go for it.”

He grins. “I’ll ask.”

My teacher friend relaxes. Me and Brad have found common ground in sciencey trivia.

“I owe you an interesting fact,” he says.

“I’ll be waiting.”

Little does he know I’ve got a trunkful of Guinness World Records facts ready to go — Robert Wadlow, the SR-71 Blackbird. You name it.

We shake hands. I look at him carefully, and I see him. A beautiful, vulnerable young man.

Then my name is called. A pupil leader says generous things about my bravery and resilience as I walk to the podium, grabbing it like I’m riding a runaway racehorse.

I wave to my teacher friend at the back. “Tell me when to stop, will you?” She smiles. I smile back. This is okay.

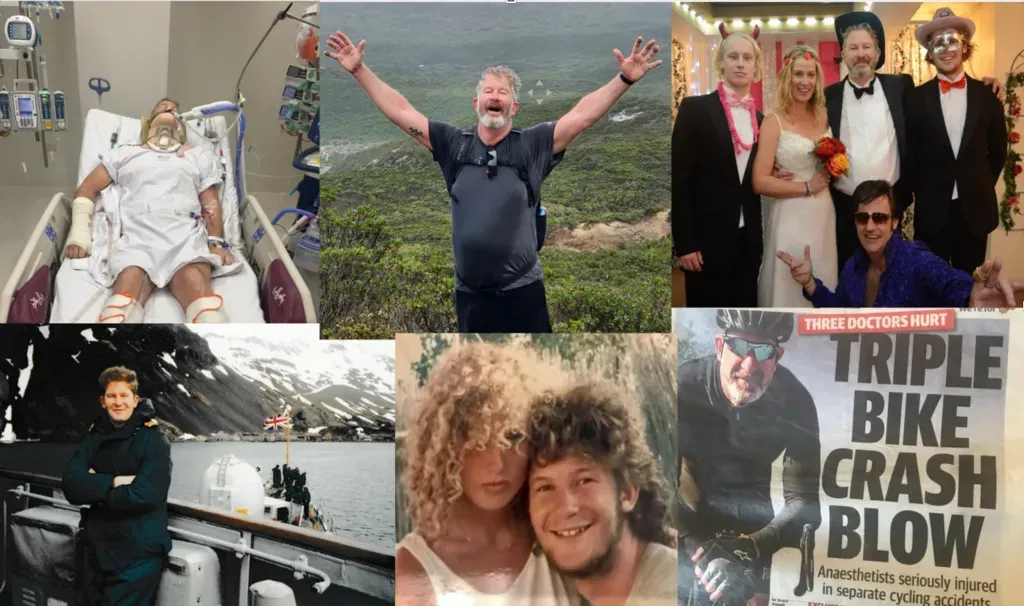

Behind me, photos flash on the screen — a boy, a naval officer, a married man, a doctor, a critically ill patient. The boys laugh. Some look worried when they see me unconscious on a ventilator.

I tell a few stories. No foreign ports, no rugby club drinking games. I manage not to blaspheme, except for a “flippin’,” which I figure is fair game. The headmaster, in his flowing Hogwarts gown, doesn’t object.

I explain how I never plan things and how sometimes that works out, and sometimes it doesn’t. Marriages and careers, accidents and injuries; take your pick.

“I’m not a patient, or a doctor. I’m just a dad and a husband now. That’s enough.”

That’s the only white lie I tell that morning.

I want to say I’m a writer too. But ten minutes isn’t enough time to explain the uncertain, uber-competitive nature of publishing, and the future.

The headmaster chokes back a tear as he thanks me, visibly moved. Then the bagpipes start, and I stagger off stage, trying to find the stage stairs through blurry eyes.

We march down the hall, the drums guiding our steps. I smile at the boys when I dare to look up.

“I need to hide for a while,” I whisper to my teacher friend, and she squeezes my hand.

I’m still waiting for Brad’s interesting fact. I bet it’ll be a good one.

Bruce Powell