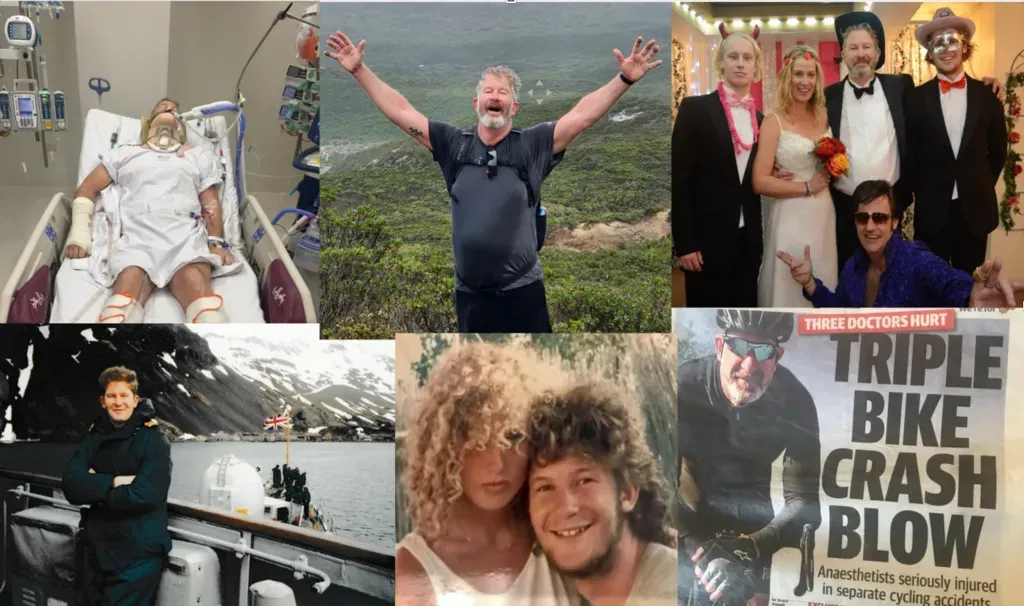

Living with PTSD: A Doctor’s Journey Through Trauma and Healing

I have PTSD. There, I said it.

Am I better off with the label?

It feels like we’ve started slapping labels on everything—grief is now depression; pre-exam nerves are anxiety. Are we just medicalising the normal ups and downs of a life that is, by nature, uncertain and often cruel? Do labels help people understand and manage their struggles, or do they just invite stereotypes and stigma?

But here’s the catch: you don’t get to diagnose yourself. You can’t just print off a PTSD certificate and start wearing the t-shirt. Without a professional’s approval, there is no official label. And without the label, there is no funded therapy, no medication, no ‘approved’ way forward.

PTSD is not just stress or sadness. It comes from real trauma—something witnessed or experienced directly—that rewires the brain. It brings nightmares, intrusive memories, avoidance strategies, emotional numbness, shame, a detachment from life and relationships. And it sticks around. PTSD isn’t a bad week or a rough month. It lingers, shaping how you see yourself and the world.

So, what if I don’t have PTSD?

I absolutely do not want to be labeled, but PTSD is a strange beast. It thrives on avoidance—pushing memories away while still letting them fester beneath the surface. It makes emotional connection very hard, even with the people you love most. But here’s the thing that really messes with my head: I don’t even remember my accident. How can I have PTSD if I don’t recall the trauma itself?

Turns out, explicit memory is not a requirement. The brain does not need crisp, detailed recollections to store trauma. The body remembers the experiences, deep inside. The mind holds onto fear and pain in ways we do not fully understand. I tried waiting it out, hoping time would be the great healer. Instead, I found myself caught in a loop of anger, depression, and denial.

Given my brain injury, my PTSD is a mix of physical and psychological wounds—meaning both therapy and medication might help, but there’s no one-size-fits-all treatment.

PTSD recovery is trial and error. Brains are messy, exquisitely complex and our understanding of brain science is still rudimentary. The most well-supported treatments rely on exposure therapy—forcing the brain to reprocess trauma instead of running from it. The idea goes back to Pavlov and his drooling dogs. He rang a bell when feeding them, and eventually, they learned to salivate at the sound alone. PTSD works in reverse—the brain pairs certain triggers with fear, long after the danger has passed. Exposure therapy aims to unlearn those responses.

Writing is my version of Pavlov’s experiment. It’s a way to revisit my trauma without tearing at every fragile scar. Structured writing therapy has an evidence-base, but even outside of formal treatment, storytelling can be powerful. Writing offers a safe space where trauma can be confronted, made sense of, rewritten such that regret and fear become acceptance and optimism.

I still cry when I try to find words that encapsulate the waking moment in the Intensive Care Unit after 6 days unconscious; hearing my son’s voice, feeling his hand in mine. Maybe I’m just slower than Pavlov’s dogs, or maybe waking from the coma—the real, psychological one—takes longer than I expected.

But writing helps.

Admitting that PTSD was a problem for me, prompted me to do some research and seek help. I don’t have a t-shirt, I don’t wear a label, nor am I seeking sympathy, but with the gentle, patient aid from family and healthcare professionals, I have created a file with advice and contact details for those who can help me when I am struggling.

I’ll get over the crash. I’ll work my way out. I’ll move on.

I’ll start by writing about my past as a doctor—who I was before that day on the Great Ocean Road. Not the pain, not the fear. I don’t have the words for that yet, and I don’t want anyone else finding them for me. It’s my story.

Once I’ve written about the past, I’ll stop looking backward.

And one day—when I’m ready—I’ll write about the crash, about losing myself somewhere on that descent. And once I’ve done that, I’ll be able to write about the future.

Just not yet.