When Thinking Saves Lives

High Performance and Cognitive Load

A young family is drifting away from shore.

At first it barely registers. The beach still looks close enough to swim to. The children are still laughing. Then the distance widens. The sand stops getting closer. Panic arrives quietly, then all at once.

The mother does what parents do. She scans the water. Counts heads. Gauges distance. Wind. Current. Time. Three children. Her mind races, pulling in every possible threat. This is not calm reasoning. It is instinct. Fight or flight has already begun.

This moment isn’t about courage. It’s about what happens to thinking under pressure.

All of us face moments where accuracy matters and the stakes are high. A crisis at work. A medical emergency. A sudden decision that cannot be delayed. When we fail to manage the moving parts, the consequences can be serious.

For fast-jet pilots, astronauts and medical first responders, these moments are routine. They train for them. For most of us, they are rare, which makes them harder to handle.

When too many things demand attention at once, thinking degrades. We simplify. We rush. We latch onto decisive actions, not always good ones. Psychologists call this cognitive load. You don’t need the term to recognise the feeling.

Think of a phone with too many apps open. It slows. It freezes. Sometimes it crashes. Human brains do something similar under stress.

Back in the water, the mother is carrying everything at once. The sea state. The children’s abilities. The distance to shore. The fear of what might happen if she gets this wrong. Time pressure makes it worse. Fatigue makes it worse. Under that load, options narrow.

In that narrowed space, she makes a decision. The strongest child should swim for help.

This isn’t foolish. It isn’t neglect. It’s a decision shaped by overload. When thinking space shrinks, people divide problems, offload risk, and choose actions that feel decisive. The aim is to reduce pressure now, even if it creates danger later.

High-performance training for medical first responders and fast-jet pilots isn’t about heroics. It exists to stop the brain from betraying you when it matters most.

Under threat, pessimism is dangerous. When the mind decides a situation is overwhelming or doomed, it stops problem-solving and shifts to damage control. Thinking collapses. The outcome often follows.

The boy’s experience in the water is different.

Alone, he decides the task is hard, but possible. That judgement matters more than strength. He doesn’t sprint. He doesn’t thrash. He floats on his back to rest. He paces himself. He removes his life jacket when it becomes a hindrance rather than a help.

These are not heroic choices. They are thinking choices.

The boy not an elite swimmer. He had previously failed a swimming test. What saves him isn’t fitness or bravery. It’s the ability to keep thinking under pressure.

Eventually, he reaches shore. Help follows. The family survives.

The remarkable part of this story isn’t that a child swam to safety. It’s that two people, facing the same threat, experienced two very different mental states. One was overloaded. One kept just enough space to think.

Humans aren’t the strongest swimmers. But when conditions allow, we are very good thinkers. Survival often depends less on courage than on whether thinking stays online.

In moments like these, that difference is everything.

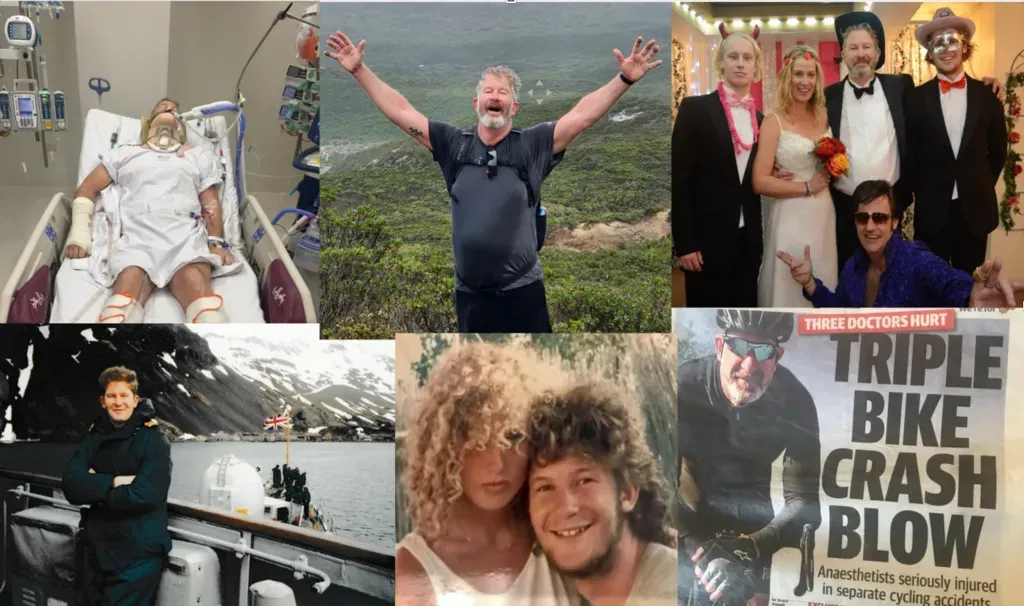

Dr Bruce Powell