Headway: Brain Injury and Me

September 25, 2024

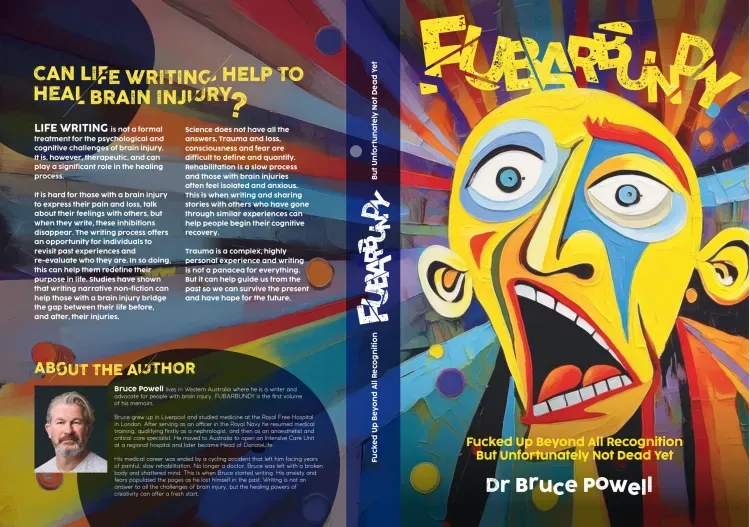

A short bio for the upcoming Headway Golf Day.

May 28, 2025

Voted the Best Poster at the World Congress on Brain Injury in Montreal. What a journey, halfway across the world to offer my poster to the World Congress and what a pleasure to be voted the winner. The conference itself was worth the trip and I look forward to maybe contributing more when the next event occurs in Valencia, Spain 2027. A massive thanks to the organising committee and all the fascianting, driven, passionate clinicians I met there. Bruce.

March 31, 2025

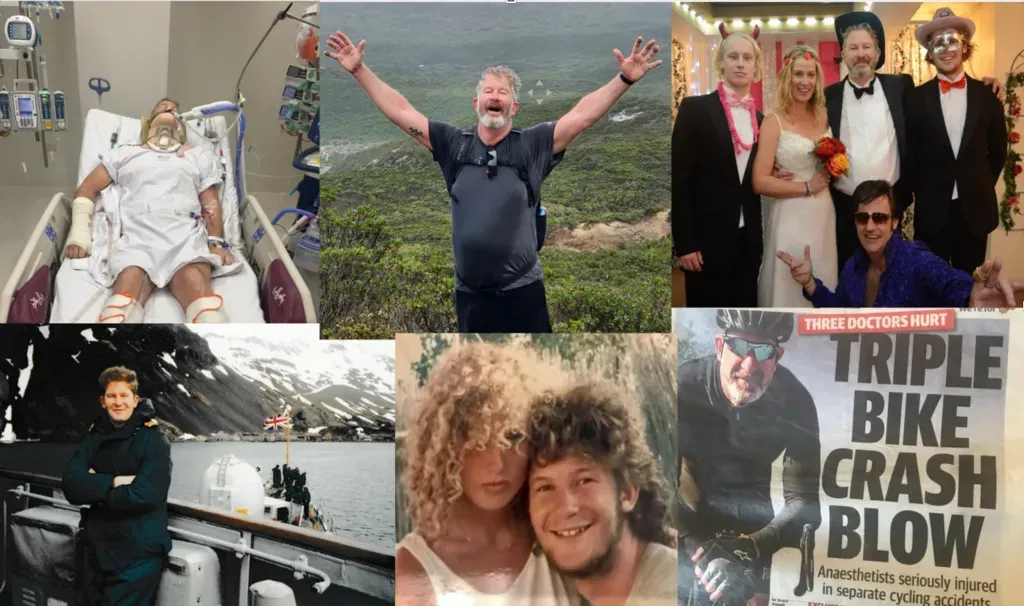

Hundreds of boys file into the school hall. Lines of plastic chairs are filled neatly, without gaps, not like a church or a footy stadium. This community sits shoulder to shoulder. Sure, they’re told to, but it looks natural. No one sits alone. No one is isolated by skin colour or footy allegiance. They wear uniforms and neat hair, sing their songs, and reply to prayers with one voice. I march in behind the shrill song of the bagpipes with other members of the assembly team. I can feel emotions bubbling in my chest. Ritalin and coffee will do that, but the low hum of bagpipes and a sea of young faces would be enough to break the most stoic of observers. I stare at the floor, steadying myself. I’ve got to stand up and speak soon. Today’s assembly is about neurodivergence and tolerance for all kinds of humans, every taste and vision. I hope none of these kids have read my grumblings about ADHD labels. I’m pretty sure they’ve got better things to do. Earlier, I met the assembly team at the Inclusive Education Centre and was introduced to Brad (not his name). He’s tall and charming. Fifteen years old, curly-topped, and smart. “I’m tired,” he says, straight off. I offer him my usual brand of sarcasm, aiming for a laugh. Big mistake. “It’s because of my circadian rhythm,” he explains. “I row. At 4:45. Every morning.” Plonker. Too busy trying to be funny instead of listening. Now I see him. My teacher friend, an expert in all things neurodivergent, shuffles closer, looking worried. My brand of humor doesn’t always read as empathy. “Your steroid levels go up and down,” I say, the nerdy schoolie in me resurfacing. “That’s why you’re cold early in the mornings.” Brad looks curious. “Really?” “Yep. When Australian athletes compete overseas, they adjust their body clocks to perform better.” “How?” “They train at night and sleep during the day.” “Maybe I should try that.” “I doubt school, or your Mum would go for it.” He grins. “I’ll ask.” My teacher friend relaxes. Me and Brad have found common ground in sciencey trivia. “I owe you an interesting fact,” he says. “I’ll be waiting.” Little does he know I’ve got a trunkful of Guinness World Records facts ready to go — Robert Wadlow, the SR-71 Blackbird. You name it. We shake hands. I look at him carefully, and I see him. A beautiful, vulnerable young man. Then my name is called. A pupil leader says generous things about my bravery and resilience as I walk to the podium, grabbing it like I’m riding a runaway racehorse. I wave to my teacher friend at the back. “Tell me when to stop, will you?” She smiles. I smile back. This is okay. Behind me, photos flash on the screen — a boy, a naval officer, a married man, a doctor, a critically ill patient. The boys laugh. Some look worried when they see me unconscious on a ventilator. I tell a few stories. No foreign ports, no rugby club drinking games. I manage not to blaspheme, except for a “flippin’,” which I figure is fair game. The headmaster, in his flowing Hogwarts gown, doesn’t object. I explain how I never plan things and how sometimes that works out, and sometimes it doesn’t. Marriages and careers, accidents and injuries; take your pick. “I’m not a patient, or a doctor. I’m just a dad and a husband now. That’s enough.” That’s the only white lie I tell that morning. I want to say I’m a writer too. But ten minutes isn’t enough time to explain the uncertain, uber-competitive nature of publishing, and the future. The headmaster chokes back a tear as he thanks me, visibly moved. Then the bagpipes start, and I stagger off stage, trying to find the stage stairs through blurry eyes. We march down the hall, the drums guiding our steps. I smile at the boys when I dare to look up. “I need to hide for a while,” I whisper to my teacher friend, and she squeezes my hand. I’m still waiting for Brad’s interesting fact. I bet it’ll be a good one. Bruce Powell

March 10, 2025

I am flying to Canada on Friday. It’s the World Congress on Brain Injury. I’m presenting a poster. That’s not what wakes me up this morning. Science meetings and presentations don’t faze me but they do remind me of the old days, when I was a medic. The thing is, Friday is a long flight—via Dubai to Montreal, a chilly and unfamiliar city. At the conference, there will be hordes of new people to engage with, hours of lectures about topics that matter to me, and long evenings trying to be sociable before finding my way back to my hotel alone. I think I’m scared. Yesterday, Sunday reminds me of my frailty. It’s intense. I spend the day wrestling with building issues and budgets. I’m going to the theatre in the evening, but that will be fine. I’ll relax once the lights go down. Brain fatigue doesn’t work like that. My friend Ann picks me up at 4 pm. She is a good person. She tells others that I am her “cultural partner”—which sounds dodgy, I know. No hanky-panky, she’s 82. I regularly accompany her to theatre and musical events when she can’t find a more broadly educated escort. I know I’m in trouble as we drive into town. “Oh yes, Dexy’s Midnight Runners! Turn it up, Ann! Drive faster, let’s go!” “Bruce, please.” “Come on, grandad, get out the way! Fuck sake.” Scary for Ann. She won’t understand what’s happening. Control, for me, is a delicate illusion that shatters under pressure. How would Ann know? She’s never seen this before. There’s a scrummage in the theatre car park, cars crawling in all directions, no one giving space, everyone staring straight ahead, muscling in and out of spots. Ann’s window is down. Big mistake. “IS THERE A FIRE?” I shout across Ann at the lady in the Porsche Cayman that’s an inch from our wing mirror. The lady’s window winds down. “What did you say?” Porsche-woman wants a fight. And in this state, I’m hungry for conflict—emboldened, invigorated. The adrenaline rush of confrontation is the only thing keeping me upright. “BRUCE, stop it.” Ann is mortified. I laugh and for a moment, I get a grip. But not really. “I’m being overcome by the stink of piss,” I yell as we take the stairwell down to the ground floor. “Bruce, please.” Next, the euphoria leaves and my anxiety grows. ALCOHOL. That’s the answer. Not really, though. The bar queue is long, and my mouth is unhinged. I moan to my fellow queuers about staffing levels. I even tell them I’m brain injured. I have never done that before. When the tannoy announces that the play is about to start, I lose it. “Sir, you must go in now, otherwise we will lock you out.” The drinks line disappears empty-handed into the dark. I can’t bear my own internal turmoil. I’m not leaving without my therapy. “Three beers, please. NOW.” The bar lady looks worried. I just stare straight ahead. She tries to apologise. “I’m not interested,” I snap. I’m rude to the usher too, but she lets me passed as the lights dim. Auto-pilot. Sit down. Drink. Drink. Two bottles straight down. Takes the edge off my terror but I’m in free fall. Ann has made sandwiches that she slips to me in the gloom. I eat eight quarters of chicken and mayo in the dark. One greedy mouthful each time; fairly sure I eat some of the clingfilm too. The usher catches Ann take a nibble of her ham and mustard and comes over to tell her off. God only knows what I would have done if the usher had shone the torch in my stuffed face. There’s a voice that only appears in my head when I am truly unhinged. Unpeel the sandwich and slap her cheeks with the mayonnaise. That’s him—that’s my inner voice. Now I’m really worried. “I’m not OK,” I tell Ann in the first interval. “Why don’t you catch a cab home?” “I don’t think I know how. Will you look after me if I stay?” I did and she does. I was planning to review the play. Osage something it’s called. Feuding families. Jealous daughters. Fighting. But I cannot. I don’t know what happened. I can’t remember. I lost the time. One minute, the family gathers for a funeral—Dad’s suicide, I think. The next, there is a woman in a dressing gown lying on the floor at the front of the stage, bawling something unintelligible as the lights dim. The lights go down, then up. I applaud but I cannot stand up. Not yet. The cast will have to forgive me for sitting with my head in my hands. I am already afraid for the exit. The stairs are steep, and the crowds will be eager to get back to the killing fields of the car park. I might fall. I might take Ann with me. Crush her skull and her ham sandwiches. This is how fatigue is for me. I should have planned the day better. It’s not fair on others. I am my own responsibility. Montreal mustn’t go this way. I’m on my own there. No “F**k Trump” T-shirt or risqué banter with immigration staff or police officers. Stay in control. Rest well. Listen to my brain. I’m going back to bed now Born Voyage.

February 6, 2025

I have PTSD. There, I said it. Am I better off with the label? It feels like we’ve started slapping labels on everything—grief is now depression; pre-exam nerves are anxiety. Are we just medicalising the normal ups and downs of a life that is, by nature, uncertain and often cruel? Do labels help people understand and manage their struggles, or do they just invite stereotypes and stigma? But here’s the catch: you don’t get to diagnose yourself. You can’t just print off a PTSD certificate and start wearing the t-shirt. Without a professional’s approval, there is no official label. And without the label, there is no funded therapy, no medication, no ‘approved’ way forward. PTSD is not just stress or sadness. It comes from real trauma—something witnessed or experienced directly—that rewires the brain. It brings nightmares, intrusive memories, avoidance strategies, emotional numbness, shame, a detachment from life and relationships. And it sticks around. PTSD isn’t a bad week or a rough month. It lingers, shaping how you see yourself and the world. So, what if I don’t have PTSD? I absolutely do not want to be labeled, but PTSD is a strange beast. It thrives on avoidance—pushing memories away while still letting them fester beneath the surface. It makes emotional connection very hard, even with the people you love most. But here’s the thing that really messes with my head: I don’t even remember my accident. How can I have PTSD if I don’t recall the trauma itself? Turns out, explicit memory is not a requirement. The brain does not need crisp, detailed recollections to store trauma. The body remembers the experiences, deep inside. The mind holds onto fear and pain in ways we do not fully understand. I tried waiting it out, hoping time would be the great healer. Instead, I found myself caught in a loop of anger, depression, and denial. Given my brain injury, my PTSD is a mix of physical and psychological wounds—meaning both therapy and medication might help, but there’s no one-size-fits-all treatment. PTSD recovery is trial and error. Brains are messy, exquisitely complex and our understanding of brain science is still rudimentary. The most well-supported treatments rely on exposure therapy—forcing the brain to reprocess trauma instead of running from it. The idea goes back to Pavlov and his drooling dogs. He rang a bell when feeding them, and eventually, they learned to salivate at the sound alone. PTSD works in reverse—the brain pairs certain triggers with fear, long after the danger has passed. Exposure therapy aims to unlearn those responses. Writing is my version of Pavlov’s experiment. It’s a way to revisit my trauma without tearing at every fragile scar. Structured writing therapy has an evidence-base, but even outside of formal treatment, storytelling can be powerful. Writing offers a safe space where trauma can be confronted, made sense of, rewritten such that regret and fear become acceptance and optimism. I still cry when I try to find words that encapsulate the waking moment in the Intensive Care Unit after 6 days unconscious; hearing my son’s voice, feeling his hand in mine. Maybe I’m just slower than Pavlov’s dogs, or maybe waking from the coma—the real, psychological one—takes longer than I expected. But writing helps. Admitting that PTSD was a problem for me, prompted me to do some research and seek help. I don’t have a t-shirt, I don’t wear a label, nor am I seeking sympathy, but with the gentle, patient aid from family and healthcare professionals, I have created a file with advice and contact details for those who can help me when I am struggling. I’ll get over the crash. I’ll work my way out. I’ll move on. I’ll start by writing about my past as a doctor—who I was before that day on the Great Ocean Road. Not the pain, not the fear. I don’t have the words for that yet, and I don’t want anyone else finding them for me. It’s my story. Once I’ve written about the past, I’ll stop looking backward. And one day—when I’m ready—I’ll write about the crash, about losing myself somewhere on that descent. And once I’ve done that, I’ll be able to write about the future. Just not yet.

January 16, 2025

Somewhere in suburbia he’s goldfishing, tornado mode, chronic score creep, happy feet. He does the front door Macarena. Keys, phone, wallet, plan? Why so chaotic? He forgot the Kiddy Coke, the Speed, Uppers, Vitamin R, R-ball, Skippy, Smarties, Kibbles & Amp Bits, Diet Coke, R Pop, Coke Junior, Jif, his Study buddy? Opening credits role. Music starts: ‘Dinna dinna dinna dinna dinna dinna dinna dinna A Deep Voice rumbles “He is vengeance. He is the night. He is ADHD-man. Defending the ‘lazy’, the ‘stupid’ and the ‘sloppy’, avenging those who feel guilty, ashamed and confused about their special powers. Unleashed on him by his own cruel fate, ADHD-man wages war against the slow thinkers, the narrow-minded and the evil multi-taskers. ADHD-man thinks outside of the box. He can’t remember where he put the box. Spontaneous, going with the flow, distractible and hyperfocused. Get tasks done and lose track of time. Can he reach the glamorous bikini-clad lady inexplicably tied to the railway line? Can he divert the onrushing freight train? Well he could have done, but he got distracted by the lizard sunning itself on the grassy embankment. He overcomes the tallest problems with a single idea and doesn’t know where he left the keys to the Scat-Mobile. He’s not a playboy. That would require socialisation. He is no billionaire either, although many of his ideas will make others rich. Either way, he doesn’t worry, just moves on. Queue Title Music Dinna dinna dinna ADHD-MAN.

January 16, 2025

Annabel lies alone in her side room, cot sides up. She can’t speak. Who has a massive stroke at 48? I’m not sure what to do. I’m resigned to another bollocking. The bow-tied neurology professor spelt out what he expected of me. ‘S-P-E-A-K to her.’ ’She can’t speak, Sir’, I plead. ‘I feel like I’m annoying her.’ ‘That makes two of us.’ I shuffle out of his carpeted office, back onto the wipe-clean 8th Floor, knock rhetorically, and re-enter the side-room. The slow steady beeping of her heart monitor punctuates the sterile silence. ‘Do you mind if I call you Annabel?’ Perhaps she’s deaf and blind? I take a gamble. “NEVER SIT ON THE BED.” The nurses say. Her face flickers. Progress? Her right arm unfolds from the lifeless left and straightens out towards me, ramrod straight, palm up, fist clenched. Now we’re getting somewhere. Her long, middle-finger unfurls itself from the fist and straightens beneath my chin. She eyeballs me for twenty two heartbeats. We connect. F-U-C-K-O-F-F she mouths. I hang the “DO NOT DISTURB” sign on her door as I leave.